News

e-Conference on Noise from Drones

The first international conference on noise from drones was held between 19th and 21st October 2020. It was originally to have been held in Paris in May 2020 but was postponed to October due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Because of the continuing pandemic, a decision was made over the summer to make this a ‘virtual’ conference using the Zoom platform, which has become very familiar to all of us, for both domestic and business use, as the pandemic has progressed. The conference was hosted by INCE Europe, the European arm of the International Institute of Noise Control Engineering. Andy and Charlie were both registered to go to the Paris conference (Andy was on the Technical Committee!) and both participated fully in the Zoom version. At Hayes McKenzie, we have been keeping a careful eye on the drone situation, because we are very aware of the potential noise implications that their inevitable wide-scale deployment will bring, and both Charlie and Alex (now gone to Dyson, sadly) carried out diploma and MSc projects, respectively, on the issue.

Pros & Cons of an e-Conference

As for many delegates, presumably, we felt some trepidation about how a virtual conference would pan out. A ‘real’ conference comes with a deal of camaraderie, opportunities to catch up with old friends and colleagues in the industry in coffee breaks, lots of debate on the subject matter both within and outside the main technical sessions and more informal social settings. And how would it feel to be staring at a screen for the duration of the formal sessions rather than being in a lecture theatre or similar venue.

The organisers had got this latter point well covered with much shorter, pre-recorded, presentations than would be usual at a real conference, and a much longer time set aside for the panel discussion which followed them, incorporating all the speakers and others besides, with questions from the ‘audience’. As well as the main technical sessions, one of which Andy co-chaired, there were also some more informal sessions, where anyone could join in. The only thing really missing was the opportunity for informal chat in breaks between sessions which the organisers are looking into for the next INCE Europe conference; the two yearly wind turbine noise conference, which will also be held in a virtual space. There were some significant advantages, of course, including lack of any travel costs, which would have been significant for those outside the EU, lack of setting aside time to travel,lack ofcarbon footprint associated with the travel, no jet lag, excellent audio and visual clarity, and the overall convenience of staying at home (or in the office for some). Albeit this included attending some sessions in the middle of the night for the Asia Pacific and American attendees although they were arranged such that both had access to at least one of the two formal sessions per day within normal working hours.

Technical Presentations

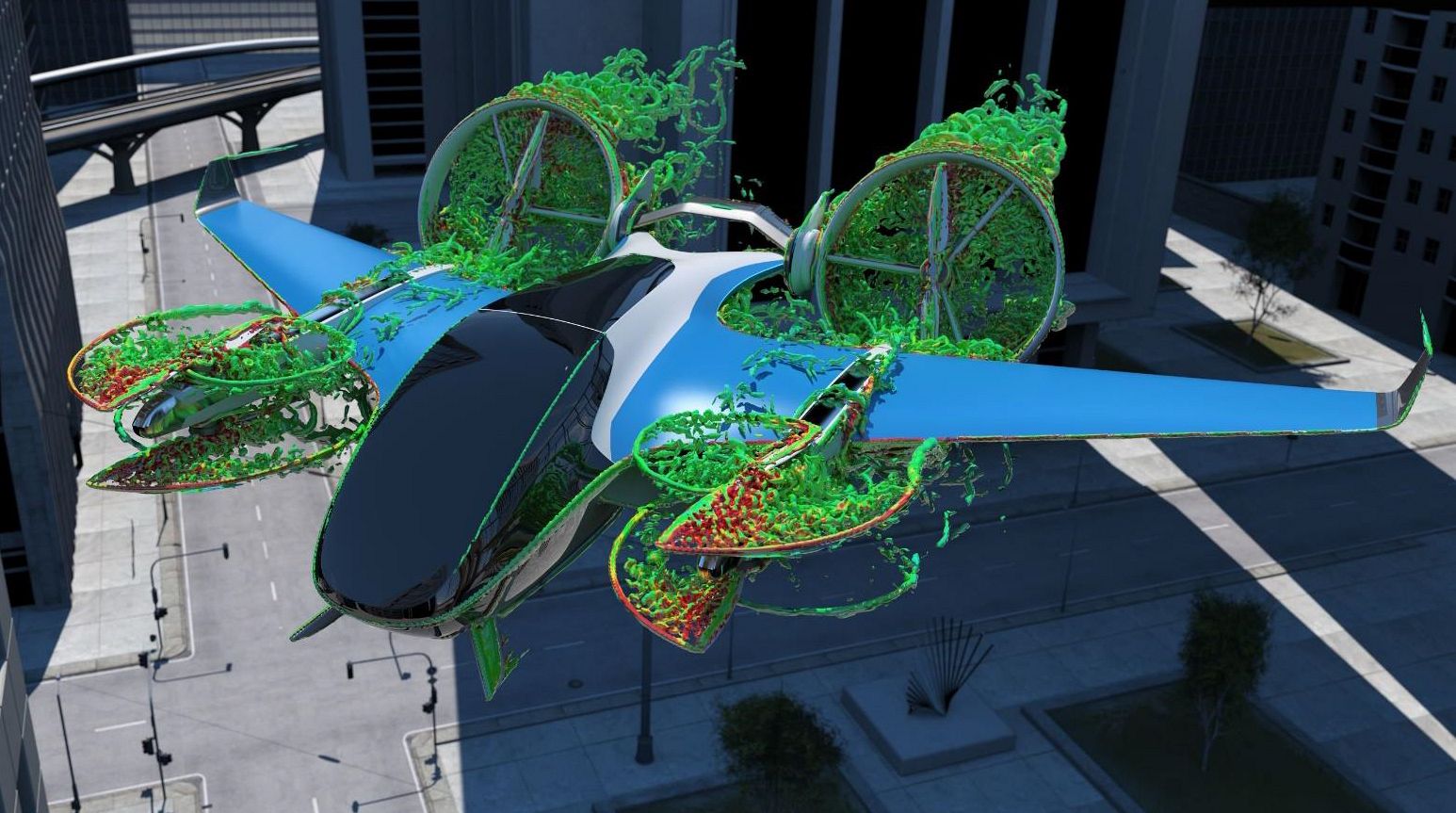

The technical presentations were largely divided into those concerned with source noise generation and those concerned with impact on community receptors. Drones can be used for an astonishing number of different purposes and there was even talk of (driverless) air taxis! Use of drones for some activities, such as aerial surveillance, has less noise impact as this will usually consist of a single drone launched from a specific location, which can be chosen at will, and a single fly-over of a specific area. What is likely to have the highest impact, however, is their use for deliveries where noise impact arises around the point of dispatch (take off, if you will, from the delivery hub), under the flight path, and at the point of delivery. Whilst fly-over noise can be expected to be minimal at typical altitudes in a sub-urban location, it will certainly have an impact in rural areas. The delivery hub is likely to be in a non-residential area but the flight paths of departing drones may well pass over the nearest housing at low altitude unless they are programmed to ascend vertically prior to commencing on the delivery route. Even with this option, there will inevitably be a concentration of noise prior to the dispersal of the delivery routes to their eventual destinations. The biggest noise impact, however, is likely to arise at the point of delivery where the drone is required to descend to relatively low altitude and hover to complete delivery of the package, be it goods from Amazon, home delivery groceries or ready meals, medical supplies, or even a single cup of coffee as was discussed at least once at the conference! In such circumstances, the noise impact on the recipient can be largely disregarded but the impact on neighbours could be quite high, particular where multiple deliveries occur over a day.

The problem is, not only the level of noise, but more particularly the character of the noise, of which various samples were presented during one of the informal sessions at the conference. This arises from the use of multiple rotors, which are a fundamental part of the way drones operate and which permit the very precise movement of which they are capable. The noise from each of these rotors interacts to produce a noise which is rather akin to that from a giant insect and, because it is the interaction which causes this effect, rather than the individual sources, this presents a significant challenge to designers concerned with minimising noise. It also presents something of a challenge to those assessing the noise because the character of the noise cannot be classified as tonal, or impulsive, which are the two acoustic features which can be, and are usually, assessed as the main contributors to noise character. Rather akin to the ‘buzz-saw’ noise, which occurs for some aircraft with modern high by-pass ratio jet engines on take-off, which Hayes McKenzie have investigated in our paper with ISVR for Applied Acoustics , it needs specific consideration outside the parameters which are normally applied to determine the kind of character correction applied as part of assessment methodologies such as BS4142.

What’s Next

All in all, the conference was deemed to be a great success by the 170 delegates from 21 countries who attended, and the intention is to hold a further conference with the eventual intention that it become a two yearly event like the INCE Europe wind turbine noise conferences, of which the 9th will be held next year. Although it is likely that any 2022 conference will be a ‘real’ conference, it is inevitable that, drawing on experience at this conference and elsewhere, there will be a virtual element to allow those for whom costs and travel time would be prohibitive, to take part.